Urban Wetlands

•“To protect, enhance, restore, and manage coastal wetland and upland habitats to benefit native fish, wildlife and plant species.”

• “To protect, restore and enhance the viability of key coastal habitats and species and preserve the region’s cultural heritage while encouraging compatible public use, education and research.”

• “To protect, enhance, and manage populations of endangered and threatened species and other species of concern through habitat restoration and population management.”

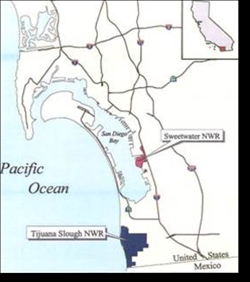

Figure 1. The location of the Sweetwater National Wildlife Reserve and the Tijuana Slough NWR (courtesy of the USFWS).

The fact that only 9% of California’s naturally occurring wetlands remain is just one of the many obstacles plaguing restoration in the region. Invasive species continue to be an issue and, in the Tijuana Estuary in particular, sedimentation loads that suffocate natural habitats are especially problematic. Cost remains a considerable factor and one of the highest hurdles. The Tijuana Estuary required $600 million in the first 25 years of restoration alone. Given the location of California’s wetlands in an urban environment, high price tags often stem from manipulating geomorphology and managing man-made structures, such as the dredging of land and the tearing down and rebuilding of roads.

Example of Restoration in Sweetwater Marsh

California adopted a “no net loss” policy towards wetlands in 1989, which means that the acreage of wetlands in the state can remain the same or increase, but not decrease. Wetland mitigation, one of the ways in which this goal is accomplished, requires the restoration or creation of wetlands to off-set for those whose destruction is unavoidable.While this method helps to maintain California’s wetland area,

Dr. Joy Zedler (Fig. 5), the Aldo Leopold Professor of Restoration at UW-Madison and researcher of S. California’s wetlands for over 30 years, was hired by Caltrans to monitor the progress of their cord grass restoration. Dr.Zedler first began taking her San Diego State University students out to California’s salt marshes in the 1980’s to show them vegetation changes along salinity gradients. Her prior research, which included understanding the mechanisms of cord grass growth, would prove beneficial during the Caltrans study.

Redefining Success

Although some might be quick to judge the restoration in Sweetwater Marsh as a failure, Zedler wouldn’t be included in that list. Despite being unable to provide sustaining habitat to the Clapper Rail, restoration efforts have successfully created habitat for other endangered species living in the marsh, including the California Least Tern. Instead of using the term “success” to define a project, Zedler likes to use the terms “progress”, saying that the word ‘success’ is a too subjective and an unclear descriptor of restoration. Progress allows for a wider range of outcomes and better demonstrates the movement towards meeting restoration criteria. Mistakes along this progression can inform new restoration efforts of what not to do and increase the probability of meeting criteria in future projects. Although Caltran’s restoration of the Clapper Rail’s habitat may have not been a total “success”, Zedler says if they had to do it again, they’d know how to do it right.

References

1. Gibson, Kevin D., Joy B. Zedler, and Rene Langis. “Limited Response of Cordgrass (Spartina Foliosa) To Soil Amendments in a Constructed Marsh.” Ecological Applications 4.4 (1994): 757. Web.

2. Malakoff, D. “Ecology: Restored Wetlands Flunk Real-World Test.” Science 280.5362 (1998): 371-72.

3. “Sweetwater Marsh National Wildlife Refuge South San Diego Bay Unit of the San Diego National Wildlife Refuge.” U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 1 Oct. 2001. Web. <http://www.fws.gov/sandiegorefuges/new/pdf/Planning_Update_2.pdf>

4. “Tijuana River Comprehensive Management Plan National Estuarine Research Reserve.”National Estuarine Research Reserve System. National Estuarine Research Reserve System, 1 Sept. 2010. Web. <http://www.nerrs.noaa.gov/Doc/PDF/Reserve/TJR_MgmtPlan.pdf>

For more information about the Tijuana Estuary, go to http://trnerr.org/

For more information about the Sweetwater , go to: http://www.fws.gov/refuge/san_diego_bay/