Lady’s Slipper Orchid

Restoration of Lady’s Slipper Orchid

Every summer the Lady’s Slipper orchid (Cypripedium kentuckiense) produces a very large flower that resembles a lady’s slipper. It is grows in old growth forests throughout the southern U.S. This orchid, however, has become increasingly rare, and there are only four plants in the entire 604,000 acre Kisatchie National Forest where it was once common.

Restoration of Lady’s Slipper Orchid in the Kisatchie

National Forest:

An Interview with Kevin Allen

By Kaci Fisher

Department of Environmental Sciences

Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803

_________________________________________________________________________

“Something’s not adding up. Out of 200 seedlings, something should have lived.” – Kevin Allen

The Lady’s Slipper orchid

Every summer the Lady’s Slipper orchid (Cypripedium kentuckiense) produces a very large flower that resembles a lady’s slipper (Fig. 2). It is grows in old growth forests throughout the southern U.S. This orchid, however, has become increasingly rare, and there are only four plants in the entire 604,000 acre Kisatchie National Forest where it was once common.

Restoring Lady’s Slipper

The Spangle Creek Laboratory determined that the orchid’s seeds were viable, and over a year later sent back a total of 900 seedlings, which were distributed to different members of the Central Louisiana Orchid Society. Two-hundred of those 900 seedlings survived to be planted in the Kisactchie National Forest.

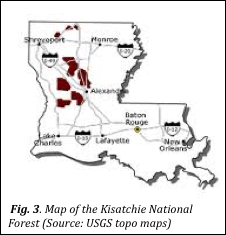

Kevin Allen (Fig. 1) was first introduced to the Lady’s Slipper orchid on a Nature Park field trip while in middle school. His interest continued through high school, where he met up with a forest botanist at the Kisatchie National Forest (Fig. 3). Allen was shown four areas in the forest where a single Lady’s Slipper had been found. He saw it as a challenge to restore these rare orchids and decided to germinate them. Allen obtained a permit from the Forest Service and pollinated the orchid. He then sent the seeds to Spangle Creek Laboratory in Minnesota to see if the seeds were viable.

The orchid seedlings were planted next to the parent orchid so as to be in an ideal environment.

Three different plantings took place over a year with each planting examining a different variable. These variables included the length of time the seedlings were grown in a tray before planting, planting in fertilized and non-fertilized soil, and different planting depths. After two years of monitoring, there was a zero percent survival rate for all experiments. Allen is now looking into the role of a mycorrhizal fungus that is known to facilitate seed germination for some orchid species.

Three different plantings took place over a year with each planting examining a different variable. These variables included the length of time the seedlings were grown in a tray before planting, planting in fertilized and non-fertilized soil, and different planting depths. After two years of monitoring, there was a zero percent survival rate for all experiments. Allen is now looking into the role of a mycorrhizal fungus that is known to facilitate seed germination for some orchid species.

Future Work

The specific fungus needed by the Lady’s Slipper orchid is unknown, so the next step is to identify it. Allen hopes that planting seeds near-by the established orchid using seed-baiting packets (Fig. 4) will get the fungus to start growing on the new seeds. If that succeeds, then the plantings can be tried again with the fungus, to see if the Lady’s Slipper can be established.

Acknowledgements

Kevin Allen, R. Eugene Turner, and David Moore.

For Further Information

Barnett, J. P. et al. (2012). Restoring the rare Kentucky lady’s slipper orchid to the Kisatchie National Forest. Native Plants 13 (2): 99-106.